There are some areas, however, where the valence bond theory falls short. Valence bond theory does a remarkably good job at explaining the bonding geometry of many of the functional groups in organic compounds. Molecular orbital theory, antibonding vs. This type of bond is referred to as a σ (sigma) bond. This means that the bond has cylindrical symmetry: if we were to take a cross-sectional plane of the bond at any point, it would form a circle. One more characteristic of the covalent bond in H 2 is important to consider at this point. The two overlapping 1 s orbitals can be visualized as two spherical balloons being pressed together. This ‘springy’ picture of covalent bonds will become very important in chapter 4, when we study the analytical technique known as infrared (IR) spectroscopy. It is not accurate, however, to picture covalent bonds as rigid sticks of unchanging length – rather, it is better to picture them as springs which have a defined length when relaxed, but which can be compressed, extended, and bent.

See a table of bond lengths and bond energies For the H 2 molecule, the distance is 74 pm (picometers, 10 -12 meters). Likewise, the difference in potential energy between the lowest energy state (at the optimal internuclear distance) and the state where the two atoms are completely separated is called the bond dissociation energy, or, more simply, bond strength. For the hydrogen molecule, the H-H bond strength is equal to about 435 kJ/mol.Įvery covalent bond in a given molecule has a characteristic length and strength. In general, the length of a typical carbon-carbon single bond in an organic molecule is about 150 pm, while carbon-carbon double bonds are about 130 pm, carbon-oxygen double bonds are about 120 pm, and carbon-hydrogen bonds are in the range of 100 to 110 pm. The strength of covalent bonds in organic molecules ranges from about 234 kJ/mol for a carbon-iodine bond (in thyroid hormone, for example), about 410 kJ/mole for a typical carbon-hydrogen bond, and up to over 800 kJ/mole for a carbon-carbon triple bond. There is a defined optimal distance between the nuclei in which the potential energy is at a minimum, meaning that the combined attractive and repulsive forces add up to the greatest overall attractive force. This optimal internuclear distance is the bond length. When the two nuclei are ‘too close’, we have an unstable, high-energy situation.

At first this repulsion is more than offset by the attraction between nuclei and electrons, but at a certain point, as the nuclei get even closer, the repulsive forces begin to overcome the attractive forces, and the potential energy of the system rises quickly.

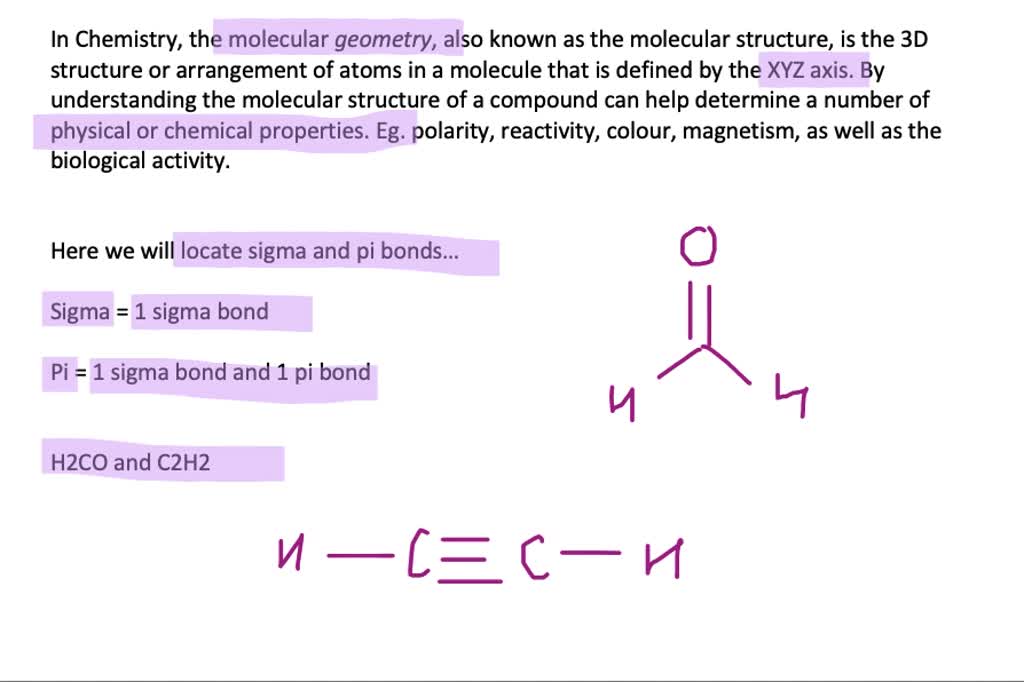

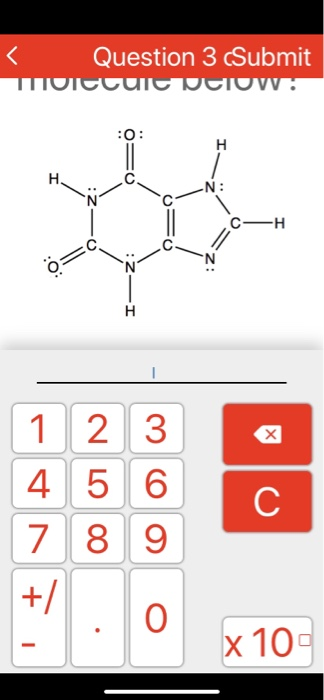

An example of sp hybridisation is ethyne, C 2H 2. Carbon undergoes sp hybridisation when it forms a triple bond, creating two equal orbitals. Sp hybridisation forms a linear structure with 180° between the orbitals. An example of sp 2 hybridisation is ethene, C 2H 4. Carbon undergoes sp 2 hybridisation when it forms a double bond, producing three equal orbitals. Sp 2 hybridisation forms a triangular planar shape with 120° between the orbitals. An example of sp 3 hybridisation is methane, CH 4. Carbon undergoes sp 3 hybridisation when it forms four single bonds and produces four equal orbitals. Sp 3 hybridisation forms a tetrahedral structure with 109.5° between the orbitals. There are three types of hybridisation: sp 3, sp 2 and sp. A double bond contains one sigma bond and one pi bond, whereas a triple bond contains one sigma bond and two pi bonds. Pi bonds occur when two pi orbitals overlap sideways and they only form within a double or triple bond. Sigma bonds occur when two atomic orbitals overlap along the bond axis and this bond always forms in a single covalent bond. When atomic orbitals overlap they form two types of covalent bonds: sigma and pi. The atom can form stronger covalent bonds using these hybrid orbitals. A hybrid orbital results from the mixing of different atomic orbitals on the same atom.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)